La rivoluzione industriale

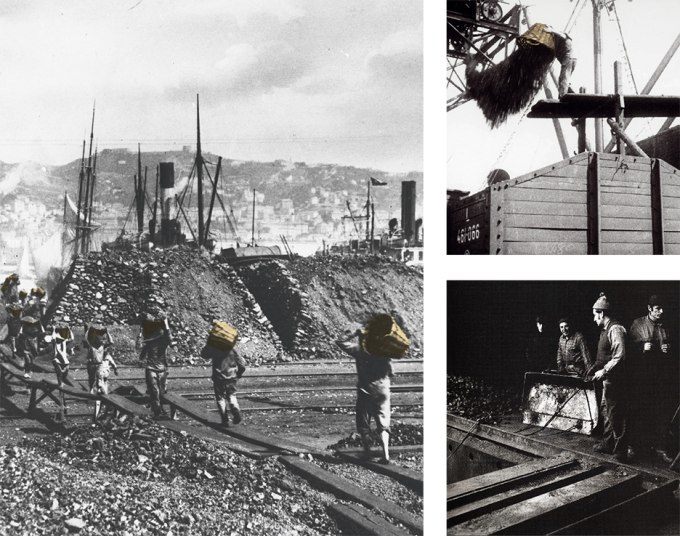

I carbunè del porto di Genova. Da notare la cesta di vimini, la “coffa”, strumento indispensabile di questo faticoso lavoro. A inizio Novecento i lavoratori in banchina si dividevano tra facchini, pesatori, caricatori e scaricatori, tutti operanti in condizioni durissime // The Carbunè working in the port of Genoa. Notice the wicker basket, or “coffa”, an essential tool for this strenuous task. At the beginning of the 20th century the dock workers were divided into porters, weighers, loaders and unloaders, all of them working under extremely harsh conditions.

Carbone e carbonai: i carbunè di Genova

La rivoluzione industriale di metà Settecento ha come elementi fondamentali la fusione e la lavorazione dei metalli e l’uso del motore a vapore. Per entrambi questi settori il carbone è indispensabile ed è per questa ragione che esso risulta essere tra i materiali di gran lunga più commerciati via nave tra Ottocento e primi del Novecento a Genova. È così che agli inizi del XX secolo, la metà dei lavoratori adibiti allo scarico merci presso la Lanterna sono i ‘carbunè’, ulteriormente classificabili, a seconda della mansione relativa allo scarico e gestione del carbone, in facchini, coffinanti (che prendevano il nome dalle ‘coffe’, ceste di vimini dove venivano messe le merci), scaricatori e pesatori.

La maggior parte delle mercanzie stivate nelle navi era per consuetudine secolare accatastata senza essere imballata, così da richiedere all’atto dell’imbarco o dello sbarco una faticosissima sequenza di operazioni di trasporto. Possiamo quindi immaginare intere stive piene di carbone venir lentamente spalate e caricate nelle coffe in grado di portare fino a 150 chilogrammi di peso ciascuna. Dall’imbarcazione, mediante una serie di passerelle – a volte semplici assi larghe trenta centimetri, ondeggianti e incurvate dal peso – il carico veniva depositato in banchina. Spesso, per mancanza di spazio, il trasbordo prevedeva una chiatta intermedia. Quando si trattava di rifornire i grandi transatlantici, il fatto che avessero boccaporti posti molto in alto obbligava a far uso di scale: file di uomini le percorrevano passandosi di spalla in spalla le coffe ricolme di carbone.

Ai primi del Novecento a Genova si caricavano quotidianamente 350-400 vagoni ferroviari destinati alle industrie del Nord Italia; con paghe da 2 a 5 lire si ricompensava una giornata di lavoro che poteva arrivare fino a 14 ore.

The Industrial Revolution

Coal and charcoal burners:

the charcoal burners of Genoa

The fundamental elements of the Industrial Revolution of the mid-18th century were the melting and working of metals and the use of the steam engine. Both these activities required the use of coal, which became by far one of the most important materials traded by ship in Genoa in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Thus, at the beginning of the 20th century, half of the workers unloading goods in the port of Genoa were known as ‘carbunè‘ (coalers), further classified, depending on the activity they carried out, in porters (or ‘coffinanti’, named after the coffers, the wicker baskets in which the coal was carried), unloaders and weighers.

For centuries, most of the goods stowed on ships were stacked in bulk, with no packaging. Loading and unloading therefore required a laborious chain of transport operations. Imagine entire holds full of coal being slowly shovelled and loaded into coffers weighing up to 150 kilograms each. The coffers were then carried through a series of gangways – sometimes simple one-foot wide planks, swaying and buckling under the weight – and deposited on the dock. Often, due to lack of space, transhipment involved an intermediate barge. When the huge transatlantic liners needed refuelling, the high hatches called for the use of ladders: rows of men lined the ladders, passing the coal-filled coffers from shoulder to shoulder.

In the early 20th century, 350-400 railway wagons a day were loaded with coal in Genoa, ready to be delivered to the industries of northern Italy; the wage for a day’s work, lasting up to 14 hours, was 2 to 5 Lire, the Italian currency of the time.