Il faro nel sistema difensivo

della Repubblica

di Genova

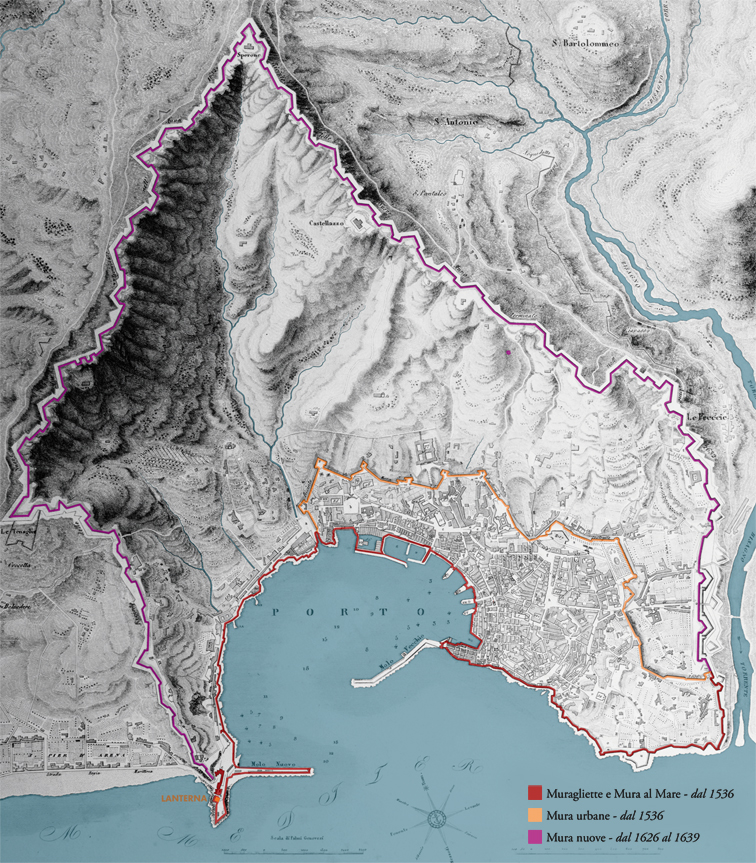

Il complesso delle mura genovesi nel 1818 // The elaborate structure of the Genoese walls in 1818.

La Lanterna fu costruita come faro di segnalazione per i marinai, ma è stata, ed è tuttora, avamposto militare (la torre superiore è oggi proprietà della Marina Militare Italiana). Una legge del 1161 obbligava ogni nave a versare una tassa per il mantenimento dei fuochi di segnalazione, che venivano però anche usati per comunicare con gli avamposti di difesa sulla costa e nell’entroterra. È per questo che fu spesso oggetto di contesa tra le varie fazioni politiche della città (per esempio nelle lotte tra Guelfi e Ghibellini nel 1318). Quando agli inizi del Cinquecento Genova si ritrovò sotto il dominio francese, Luigi XII fece innalzare, proprio a ridosso della torre, la fortezza della Briglia per controllare la città. Nella lotta per l’indipendenza, fu distrutta dai genovesi a costo di gravi danni per il faro che venne infine ricostruito come lo vediamo noi oggi, solo nel 1544.

Nel 1536 la cinta delle mura cittadine seguiva con molta precisione il perimetro della città costruita. Questa vicinanza con gli edifici abitati comportava tuttavia un grosso limite alla sicurezza, in quanto le artiglierie nemiche di nuova concezione erano in grado di creare danni rilevanti agli edifici troppo esposti agli attacchi di un eventuale esercito nemico. È così che nel 1625 si decise di costruire una nuova cinta di mura capace di difendere adeguatamente la città: due bracci che dal mare – uno partiva dalla Lanterna – salgono ancora oggi fino alla cima di monte Peralto, sfruttando la favorevole conformazione del terreno che crea una sorta di anfiteatro naturale intorno al golfo. Genova divenne in breve tempo una delle città meglio fortificate d’Europa: lunga quasi 20 chilometri, di cui circa sette lungo la linea di costa, strutturata su un insieme di 16 forti principali e 85 bastioni, racchiude un’area di 903 ettari.

The lighthouse in the Republic of Genoa’s defence system

The lighthouse, aka Lanterna, built as a beacon for sailors, was also and still is a military outpost (the upper tower is now property of the Italian Navy). A law dating back to 1161 obliged every ship to pay a tax for the maintenance of the signal fires, which were also used to communicate with the defence outposts on the coast and inland. This is why it was often the object of contention between the city’s various political factions (for example, in the battles between Guelphs and Ghibellines in 1318). When Genoa fell under French rule in the early 16th century, Louis XII had the Briglia fortress built right next to the tower to exert control over the city. In the fight for independence, the Genoese destroyed the fortress, causing unfortunate damage to the lighthouse as well. Only in 1544 was it finally rebuilt as we see it today.

In 1536, the city walls followed the perimeter of the city very precisely. Their proximity to the residential areas, however, posed a major security threat, since new-generation enemy artilleries were now capable of causing significant damage to buildings too exposed to enemy attack. To increase security, in 1625 a new set of walls was built to better defend the city: they featured two flanks that from the coast – one starting from the lighthouse – stretched all the way up to the top of Mount Peralto, exploiting the land’s natural configuration that creates a sorf of amphitheatre around the gulf. Genoa quickly became one of the best fortified cities in Europe: 19 kilometres of walls, that is 7 miles of walls of which 4 along the coastline, with 16 main forts and 85 bastions, enclosing an area of approximately 2200 acres.